How much protein do you really need per meal? I’ve been consistent with my answer—approximately 20 grams of high-quality protein—since I first wrote my protein series over a year ago. Nevertheless, it’s a question that I’m likely to keep exploring, if for no other reason than because there are so many other nutritionists out there who think differently.

My recommendation is based off a few studies (1,2,3) that all show a plateauing of muscle protein synthesis right around the 20 gram per meal mark. There are also studies that demonstrate this effect indirectly, such as this one. No study has provided evidence that more than 20 grams is helpful for an athlete (with a couple of circumstantial exceptions, one listed in the next paragraph), nor has any study demonstrated that fewer than 20 grams can provide an equivalent benefit in any athletic scenario; they’re consistent.

Given the consistency of the results, it’s improbable we’ll one day discover we were completely off. I have no doubt we’ll expand upon and append this 20 gram figure—as an example, with the possibility that many elderly individuals may need greater amounts of leucine (and therefore protein) to generate a similar response due to a blunted protein synthesis response—but I would be surprised if we ever discarded 20 grams as an important figure and went with, say, 40 grams instead.

Yet recently, a study came out that more-or-less suggests that 20 grams isn’t universal, and that 40 grams is likely better! With a title of “The response of muscle protein synthesis following whole‐body resistance exercise is greater following 40 g than 20 g of ingested whey protein” they cut right to the chase—but looking within the study, we can find plenty of reasons to doubt this conclusion.

Why? Let’s take a look.

What the Study Actually Examined

It’s important to note right up-front that the study didn’t intend to demonstrate the superiority of 40 grams of protein over 20 grams—and I’ll discuss why this is important a little later—but rather wanted to examine whether more muscular young men would benefit from larger amounts of protein than less muscular ones. This is a great question, and even if we can be mostly certain based on other studies that the answer is “no”, it’s worth investigating further in a more direct manner.

To test their hypothesis (that more muscular participants would benefit from more protein), the researchers…

- Recruited 56 young men (average age 22) and divided them into two groups:

- Group 1 [Average] of 15 total participants, with an average weight of 169 lbs (76.8 kg)

- Group 2 [Muscular] of 15 total participants, with an average weight of 216 lbs (98 kg)

- [The remaining 26 didn’t fit within these categories and were excluded]

- Assigned each group in a crossover design to either 20 grams or 40 grams of whey protein, so both groups experienced both doses of whey by the end of the study with a two-week washout between trials.

- Provided identical training preceding the whey intake.

When the trial was over, what did the researchers find? Contrary to their hypothesis, they discovered that the two groups responded statistically the same to the protein they were given. It didn’t matter that one group had an average of 39 lbs (or 17.6 kg) more muscle, they both got the exact same benefit from it—whether 20 grams or 40 grams. This is some great confirmation that overall muscularity doesn’t matter when eating protein, and that skinny climbers need just as much protein as football linebackers (or vice-versa).

But then the researchers went an unwarranted step further and started parsing data in a way they didn’t originally intend to and in a way they didn’t build their study to examine. Within the data, they saw that the participants who ingested 40 grams of protein had more muscle protein synthesis than those who ingested 20 grams, and took this as evidence that 40 grams is superior to 20 grams. Unfortunately, their data was never built to support this conclusion.

20 Grams or 40 Grams?

This isn’t the first study to measure muscle protein synthesis after ingestion of 40 grams of protein. The three studies I linked to in the second paragraph of this article all used 40 grams (or roughly, in one case) as their upper limit. Unlike the article we’re discussing today, however, they also used smaller amounts, right down to 0 grams of protein. This is important because it’s hard to tell what a plateau looks like without the cliff leading up to it! From a cliffless angle, a plateau might look like a shallowly sloping hill.

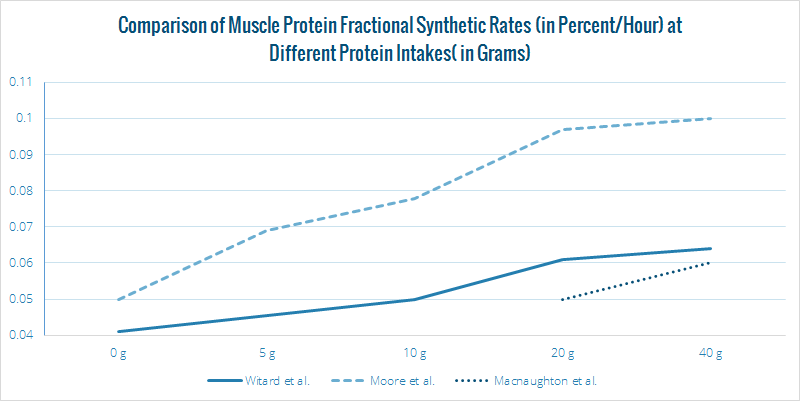

To demonstrate, I took the data points from two of the studies which used protein in the amounts of 0, 5, 10, 20, and 40 grams and plotted the rate of muscle protein synthesis (as measured in fractional synthetic rate percentage per hour) compared to what we have in this recent study (I didn’t use the third because, like this one, it only included two intake points):

The most recent study, by Macnaughton et al. and visualized as the dotted line, shows what sort of plateau we’re looking at. The dashed and solid lines represent studies that showed a statistically significant difference between consuming protein in the amount of < 20 grams per serving and between 20+ grams per serving—but not between 20 grams of and 40 grams. You’ll note that muscle protein synthesis doesn’t actually flatten in either study at 20 grams, it just slows down, and it does so at a rate that suggests there is nothing more to gain after around 20 grams of protein; at the end of the day, the amount of extra muscle you’d accrue by doubling your 20 gram protein intake per meal is insignificant.

Of course, if we were only looking at the difference between 20 grams and 40 grams (go ahead and block out the 0-20 gram data with your hand), then all three have similar looking trends. If those data points were never measured, the difference might even be statistically significant. But that’s not the real picture—the real picture is what happens as we move from “not eating protein” to “eating a little protein” to “eating a moderate amount of protein” to “eating a lot of protein”. In this picture, it’s clear that some big changes happen between “no protein or a little protein” and “a moderate amount of protein or a lot of protein”, but that the changes between “a moderate amount” and “a lot” are comparatively minuscule.

This is where it becomes important to note that the researchers didn’t actually set out to test the 20 vs. 40 gram hypothesis, but a different one entirely. I don’t doubt that their finding is “real”, but without designing the study around the other significant data points, it’s hard to know its actual significance.

Specious Reasoning for the Difference

With this “discovery” in hand, the researchers go on to provide a rationale for how their finding may fit into the rest of our collective knowledge on protein and muscle protein synthesis. I should note that this is normal—regardless of the findings of a study, the authors will spend a few paragraphs explaining how this study adds to, counters, changes, or otherwise alters our understanding of the topic and provides some direction for future hypothesis testing.

The rationale is often interesting, but in the case of this paper it’s a little boggling because it brings the whole study full-circle in an unintended manner. As an explanation for why 40 grams may have been shown to be superior in this paper when it never has before, they explain that most other papers only used lower-body exercises while theirs used full-body exercises. To this end, they write “we believe the amount of muscle exercised is the most likely explanation for the differences in results observed between this study and previous studies.”

Let me clarify that further:

The researchers set out to determine whether men with more muscle needed more protein, discovered that they didn’t, but along the way found a difference between the rates of muscle protein synthesis for 40 grams and 20 grams of protein. To explain this difference, they suggest that whole body exercises use more muscle than leg exercises alone, and that because their participants were using more muscle than previous study participants, they needed more protein.

Literally, this is exactly what their study just failed to demonstrate! Using more muscle for an exercise (in the form of being 40 lbs beefier) did not in fact necessitate greater amounts of protein, but made zero difference. So why would using more muscle across the body make a difference?

Granted, being more muscular and using more muscle groups are not the exact same thing, so there could be some other factors at play, such as the total number of muscle fibers being activated. But at the end of the day, we also know that triggering muscle protein synthesis is about reaching a plasma threshold (which is determined by protein intake and absorption alone), not delivering x amino acid units to the muscles that need them, where x must be divided by the total overall muscular need. If the latter was the case, then we would expect bigger people who have more amino acids stockpiled in their muscles to need more amino acids to repair them, which is not the case.

Wrapping Up the Debate… For Now

The thing to keep in mind through all of this is that no one has ever argued that consuming 40 grams of protein does absolutely nothing more than consuming 20 grams. The argument is that 40 grams doesn’t do anything of particular importance compared to 20 grams. You will always find slightly higher muscle protein synthesis after 40 grams, but only by a small amount that is almost certainly not going to make a big difference in the real world. Thus, 20 grams is fine for maximal muscle protein synthesis.

The study I examined above doesn’t do much to change this. It showed a difference between 20 grams of protein intake and 40 grams, but it fails to show how they compare to 0 grams or 10 grams. As I said, we would expect to see a difference between 20 and 40 grams, we just would also expect it to be insignificant compared to the difference between 0-10 and 20 grams. Without those lower intake points, it’s tough to assess the significance of the findings.

There is more work to do here; I’m all for poking and prodding in order to expand our knowledge. But we have to set out with clearly defined hypotheses. It’s bad scientific behavior to test Hypothesis A, get a negative result, then spin the article as a positive finding for untested Hypothesis B. It’s unfortunately common, but bad. Here’s to hoping we see less of it in the New Year.

I understand the 20 grams of protein every 3 hours or so. My question is regarding different kinds of protein and how fast your body asimilates them. Protein shake should be asimilated pretty fast, but eggs, meat. If you ingest a protein shake (20 grams) and two hours later you eat chicken breast (20 grams). Those 20 grams of protein from the chicken breats shpuld be asimilated by your body an hour or more after eating; so the 20 grams every 3 hours would depend on how fast or slow you digest th protein you take, no?

Thanks, I am bad explaining, hope i made myself clear enough

Tony

It’s a good question, and the honest answer is we don’t understand enough about protein kinetics (the overall rate of digestion and absorption of protein) to makeexam more than broad statements about the timing of protein intake. We do know a few things, however:

Based on these facts, we might assume that faster proteins would encourage more frequent feedings closer to the 3 hour mark while slower proteins might encourage less frequent—but this would also preclude the notion that slower proteins are inherently worse than faster proteins at building muscle, which seems very unlikely. What’s more likely is that there is something else going on vis-a-vis the way protein kinetics resolve when comparing slow- and fast-digesting proteins, and that they both are ultimately treated very similarly by our body.

At any rate, the best evidence we have suggests that as long as your protein is of high-quality, we should expect it to perform similarly, and thus the question of how protein kinetics affects muscle protein synthesis is mostly academic. It is a fascinating question, but not worth worrying about if your only concern is getting the most from your workouts!

The comparison of muscle fraction synthetic rate is the y axis of percent per hour is 0.04 4% or 0.04%?

It’s 0.04%.

Great article! Are there any additional studies that test the 10 to 30 gram range in more detail? For example, is it really 25 grams or 18 grams?

The best we have is this study which examined the difference in muscle protein synthesis across 12 hours when an equivalent amount of protein was fed as either 10 grams every 1.5 hours, 20 grams every 3 hours, or 40 grams every 6 hours. The 20/3 group had significantly better results, suggesting that neither 10 or 40 grams is as good as 20. As to whether an amount like 25 or 30 could provide better results, it’s possible, but if it did I would expect it to be a clinically insignificant amount—especially when we consider that our standard measure (muscle protein synthesis) has a much greater apparent acute effect than a chronic effect, which is to say that many things might spike muscle protein synthesis in the short-term for the purpose of a trial, but we don’t really know if that response would continue over time (and have reason to suspect it probably wouldn’t, or rather, would be mitigated).

The other thing to keep in mind is that “protein” is really just code for “amino acids”, and the amino acid profile of different foods is sufficiently different (even if similar) that it would be hard to come up with a precise figure. If we were going to examine a single trigger amino acid then we’d look at leucine, in which case we’d be looking for meals that contain at least 1.5 grams of leucine (and all the rest of the essential amino acids, as well, of course). That threshold is reached with different amounts of single protein sources—3 eggs, for example (18 grams protein), or 3 ounces chicken (19 grams protein), or 1.25 cups of cooked black beans (19 grams protein). So, most high-quality protein sources hover around that 20 grams mark, even if they’re slightly off, lending more credibility to the 20 gram figure even if we don’t have extensive data exploring 20 grams compared to 15 or 25 grams!

Why does the studies keep mixing up 20g of protein with 20 g of whey. 20 g of whey is not all protein, it contains about 13-16 g of protein and not 20 g. So the question is, does 20 g of pure protein maximize MPS or 20 g of whey ( which is about let say 15 g of protein). Which one is it, can you clarify this for me pls.

In the study discussed in this article (and most studies I’m aware of), whey protein isolate is used (which is 90% protein by mass)—so a 20 g serving of whey would have roughly 18 g of protein. Since we don’t have a data point for the effects of 18 g PRO vs 20 g PRO in this study, we can’t really say how much of a difference it makes, but most likely it’s fairly small, at least compared to a larger gap like 15 g to 20 g. When we feed in knowledge from other sources—e.g., this study on how leucine affects muscle protein synthesis—we would say it’s not really about “total protein”, but also protein quality and leucine content. A whey protein isolate contains 2+ g of leucine per 20 g serving (18 g total protein), and is an easily digested and absorbed protein, so a 20 g serving would most likely be adequate to fully trigger muscle protein synthesis even though it contains only 18 g of protein.

Ultimately, I use the 20 g protein figure more as an easy reference, because if you get 20 g of (high-quality) protein in a meal then you’ll get everything you need. In reality, some protein sources are probably fine in slightly smaller quantities (mostly animal protein sources). You’re still looking for 17+ g protein in a meal even with these, though.