I see carbohydrate backloading pop into my news feed from time to time. Usually, it’s being promoted as an easy dietary trick either to improve weight loss or to build more muscle—everyone loves these outcomes, of course, so the topic has persistent (if somewhat phasic) popularity.

The basic idea behind carb backloading is simple: for the majority of the day, you eat only fats and proteins. Only in the late afternoon or evening do you add carbohydrates, at which point you have no real restrictions, you can consume them to your heart’s content. In this way, carb backloading is a lot like a type of intermittent fast—or perhaps only really like the modified version I’ve recommended in the past, where you continue to eat a normal amount of protein at regular intervals.

Regardless, the premise rests on the same creaky hinges: change the timing of when you eat (but not necessarily the food or amount) and you’ll unlock a biochemical, physiological advantage—and then a few months later, boom, you’ve got a six-pack. Sound a little too good to be true? That’s because it probably is; let’s dig into the concept to see why, though.

“Circadian Insulin Sensitivity Variation” Is the Word of the Day

It’s four words, I know, but it’s the concept you’ll occasionally seen used to scientifically justify carb backloading. There’s a lot to go over in those four words, so we’ll break it down one part at a time.

To begin with, there’s insulin and insulin sensitivity. Insulin is an anabolic hormone whose main job is to help glucose and amino acids enter muscle cells. Sometimes there’s just too much glucose to squeeze into the muscle cells, though, and when this happens insulin pushes the glucose into fat cells where it can be converted to body fat.

Insulin, like other hormones, follows a circadian rhythm—meaning it has a 24-hour cycle. Within this daily rhythm, insulin sensitivity peaks in the morning (or in the hours you normally awaken, anyway).

Normally, we think of insulin sensitivity as a good thing. Type 2 diabetics have insulin resistance, and everyone knows that’s a bad thing, so why would insulin sensitivity be any different? Well, according to the carb backload logic, insulin sensitivity is bad (at least in the morning) because our fat cells become sensitive to insulin as well as our muscles. Hence, more carbs can enter the fat and we get fatter. If you eat carbs later, on the other hand, you’re body is more resistant to them and and they’re less likely to be taken up by the fat. And, if you work out in the evening, you get bonus points because that will specifically increase muscle cell insulin sensitivity, which means even less glucose will become fat.

The Science, or What There Is of It

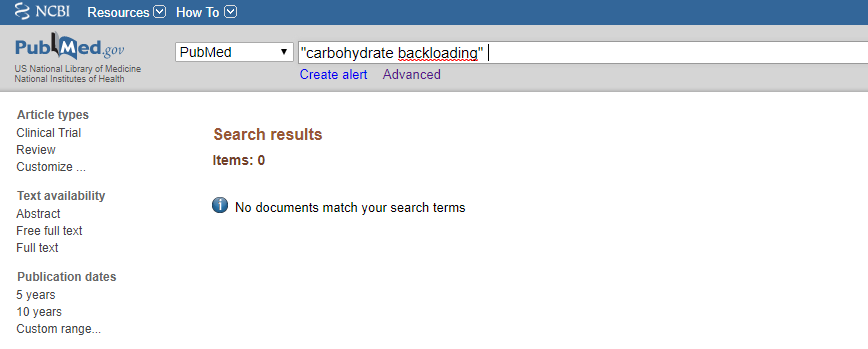

With such a scientific-sounding explanation, you might imagine there is a good amount of research on the topic! You would be mistaken. This is a screenshot of what pops up when you search PubMed for “carbohydrate backloading”:

You can use different words and different search tools (like Google Scholar), but the result doesn’t change. To date, there have been zero studies specifically on carb backloading or whether it actually does anything.

To justify it as a concept has, therefore, taken a bit more creativity. Two studies form the foundation of the argument:

- A study from 1997 that demonstrated greater retention of lean body mass when larger meals were consumed in the evening (versus morning).

- A more recent study (2011) that showed slightly greater weight loss when carbohydrates were eaten mostly at dinner.

Beyond these two studies, there are perhaps a handful more that are used here and there in justification, but they’re never directly relevant, and they always require a bit of creative application. And hey, that’s okay—sometimes creative application is needed, and it’s not always inappropriate. But in this case, we should be clear that these studies are a tiny island in a vast sea of weight loss data that mostly says carbohydrate timing doesn’t matter; extrapolation simply doesn’t seem appropriate.

Since there isn’t really science to back up the carb backloading theory, most of the arguments you hear in favor of carb backloading are anecdotal, and you know how I feel about anecdotal evidence! In truth, though, there might be something to these anecdotes—but we’ll get to the reason why a bit later.

You Can’t Biohack Muscle Gain or Fat Loss

Your body can’t be tricked into not storing carbohydrates as fat when it needs to. The good news, though, is that storing carbs as fat is at the very bottom of the priority list, mostly because it’s highly inefficient (we lose energy in the carb-to-fat conversion process). That means it’s basically the last thing we’ll do when we eat carbs, and it doesn’t happen just because we happen to be insulin sensitive at a given time.

Throughout the years, we’ve seen in repeated studies that carb-to-fat conversion is extremely low, even when study participants are massively overfed carbohydrates. In an overfed diet, it took around 500 grams of carbohydrates before conversion of carbs to fat began to cause body fat accumulation. In a normal diet, carb-to-fat conversion yielded approximately half a gram of fat per day. This doesn’t mean we’re not storing any fat on these diets, of course, because we still are when we overconsume calories—instead, it means we’re storing the dietary fat we’re consuming (much more efficient) and using the carbs for other purposes (glycogen repletion, for example).

With this in mind, “circadian insulin sensitivity” is almost completely irrelevant to how much fat we’ll gain from a carbohydrate-containing meal. What’s much more relevant is how much liver glycogen you need, how depleted your muscle glycogen is, and what your blood glucose level is. Only when all three of these factors are adequate does our body resort to storing carbs as fat, and evidence suggests that doesn’t happen very often, insulin sensitive or not.

Similarly, you won’t increase overall fat burning if you avoid carbohydrates in the morning—or if you do, you’re simultaneously increasing dietary fat intake and thus storage, and so there’s no net change. No matter where or when your calories come, the bottom line remains the same: your total caloric need. If you consume more calories than you can use, you’re going to gain weight.

Despite It All, Carb Backloading Can “Work”

Carb backloading is nonsense from a scientific perspective, but for an “average person” it might work better than other dietary strategies. It’s not because of circadian insulin sensitivity or reduced de novo lipogenesis or anything like that, though, but rather because for the average person it’s a simple form of nutrient timing.

Carb backloading is a blanket concept that implies all you need for good results is to push carbs to the end of the day. Blanket concepts are limited and often inaccurate, though. Nutrient timing is a specific concept that says we can take better advantage of carbohydrates by timing them in and around workouts. Since most adults work 9-5 and go to the gym after the office, backloading carbs effectively does this. It helps them reduce their energy intake during the sedentary portion of the day and then increase it (specifically with carbs) immediately before, during, and after their workout. They’re accidentally allowing carbs to better replenish glycogen, increase muscle protein synthesis, and improve recovery.

It breaks down if you’re a before-the-office gym-goer, though, and that’s a problem. Now, instead of carb backloading being an accidentally effective strategy, it’s an accidentally terrible strategy that leads to decreased energy and performance. While you’ll still replenish glycogen, you push the timeline out eight hours, ensuring you don’t replenish much or anything while at the office. If you also sometimes hit the gym afterwards, you’ll be just as wiped in the evening as you were after your morning workout!

For the average person, carb backloading can also “work” as a form of light caloric restriction. Anytime you eliminate a major source of calories from your diet (even transiently), you typically wind up consuming less total calories. When you add carbs back in at dinner, you’re probably not gorging enough to completely make up for those calories—and if you are, you’re not magically developing a six-pack! When this mild caloric restriction is paired with consistent exercise, some people may certainly notice improved weight. Truly, though, it’s not because of the backloading; it’s because of a reduced caloric intake and increased activity.

In the sports nutrition pyramid I’ve written about, carb backloading is like a “cheat version” of nutrient timing (tier II). It’s an oversimplification of the concept, and it might backfire on some people, but for your average 9-5er who goes to the gym only in the evening, it’s more effective than no nutrient timing at all. Ultimately, it’s better to understand the importance of nutrient timing rather than just blindly hope you’re doing it right.

Should You Backload?

I have a confession to make: a lot of the time, I (technically) carb backload. When I’m not training hard, or not going outside or to the gym, it just fits naturally with my normal pattern of eating. When I increase training intensity (as I am right now) or am planning on exercising before the evening (which is most of the time), I eat carbs throughout the day and increase them further during my workout window. I use carbs to accomplish my goals, and sometimes my goals are just to eat how I want because I’m not in a specific training or performance phase.

I would never tell you to backload your carbohydrates because it’s not a scientifically sound or effective strategy; there’s no evidence it does anything. I will tell you that you should be timing your carbohydrates to your workouts, which is to say eating more carbohydrates directly before, during, and after your workouts. If you’re training hard, you would also benefit from periodizing your carbohydrate intake to be even higher, knowing that you can decrease carbs again when training slows down.

Carbohydrate backloading is a pseudoscientific concept, but for the office worker going to the gym a few times a week after work it’s probably better than their current dietary strategy. Timing is a useful tool, but we can do better than the overly simplistic timing encouraged by backloading, and we’ll get better, more consistent results.

Hello Brian! I was wondering if taking iodine supplements would affect backloading at all? I heard, since I’m growing, I should have a good amount of iodine a day so I’m taking these to help. Should I not?

It’s probably unnecessary since we only need trace amounts of iodine and since salt is iodized. In the case of an iodine deficiency, a larger amount such as found in the supplement you referred to would aid in faster repletion, but it’s otherwise unnecessary.

Your site doesn’t allow me to post links. It is sometimes known as carbohydrate concentration. Look up “carbohydrate concentrated diet”

See also articles by Sofer on Pubmed. Here’s one: Sofer S et al. Greater Weight loss and hormonal changes after 6 months diet with carbohydrates eaten mostly at dinner.

Idea of backloading, which I understand here simply as a carb time-restricted feeding, comes from insulin spikes caused by carbs (glucose) intake, not neccessary from its circadian spikes alone. Insulin is obviously lipolysis inhibitor and lipogenic inducer, which prevents quicker fat loss. This is the whole idea of eating more carbs in one go, so you can maintain lipolysis for longer periods od time. The matter of its relevance for training and progress in climbing is another story, quite interesting to be studied.

The article is year-old I see, so I don’t know if anyone visits 🙂

Idea of backloading, which I understand here simply as a carb time-restricted feeding, comes from insulin spikes caused by carbs (glucose) intake, not neccessary from its circadian spikes alone. Insulin is obviously lipolysis inhibitor and lipogenic inducer, which prevents quicker fat loss. This is the whole idea of eating more carbs in one go, so you can maintain lipolysis for longer periods od time. The matter of its relevance for training and progress in climbing is another story, quite interesting to be studied.

The article is year-old I see, so I don’t know if anyone visits 🙂

“It breaks down if you’re a before-the-office gym-goer, though … While you’ll still replenish glycogen, you push the timeline out eight hours, ensuring you don’t replenish much or anything while at the office”

Not always true. It depends on your glycemic status. In fat-adapted endurance runners, glycogen gets replenished by gluconeogenesis. Jeff Volek’s FASTER study, and its muscle biopsy results of athletes after a 3 hour training run, show how quick that replenishment of muscle glycogen can be.

There are many studies about carb absorption and GLUT transport in muscle cells after resistance training, which is the basis for CBL. Your article seems to be in bad faith, searching for a very rarely used combination of terms in quotation marks…

If you read the article then you know I address the increase in muscular insulin sensitivity during exercise and that I’m mostly addressing the nonsense that is circadian nutrient timing (which has nothing to do with resistance exercise-based insulin sensitivity). There’s no bad faith here, just helping the reader understand the science (or lack thereof) behind certain nutritional concepts.

If I recall correctly, their muscle glycogen was also severely compromised compared to a carb-adapted athlete, which makes sense since they metabolically have shifted away from carb usage and the body has down-regulated the enzymes for carb metabolism. At any rate, for most athletes the replenishment of glycogen with gluconeogenesis isn’t ideal since that means we’re recovering muscle glucose using muscle protein, and it’s furthermore not challenging to recover muscle glycogen with a bit of carb intake—no need to delay it based on nutritional dogma.