Occasionally, I come across articles that try to simplify sports nutrition by dispensing with most common “good practices” as unnecessary (like nutrient timing, macro goals, etc.). Usually, their core message is that you should just follow your instincts—eat what you want, when you want, and not worry about the specifics.

I get why they’ve adopted this approach—it’s hard and often frustrating to put the time into good sports nutrition; we all want nutrition to be easy, to require no more effort than simply listening to our body. Unfortunately, there’s a long history of sports science research that indicates that following one’s instincts with sports nutrition is no more effective than using instinct to create a training plan. This isn’t surprising, because what we call “instincts” are not actually instincts after all, but rather habits developed over our lifetime—and habits can vary wildly.

There is a benefit to simplifying things, however. Sports nutrition doesn’t have to be all or nothing—there are plenty of steps between for those who want to gain some benefit without devoting their life to it. And if you adhere to even the basics of good sports nutrition, you can expect a lot of benefit.

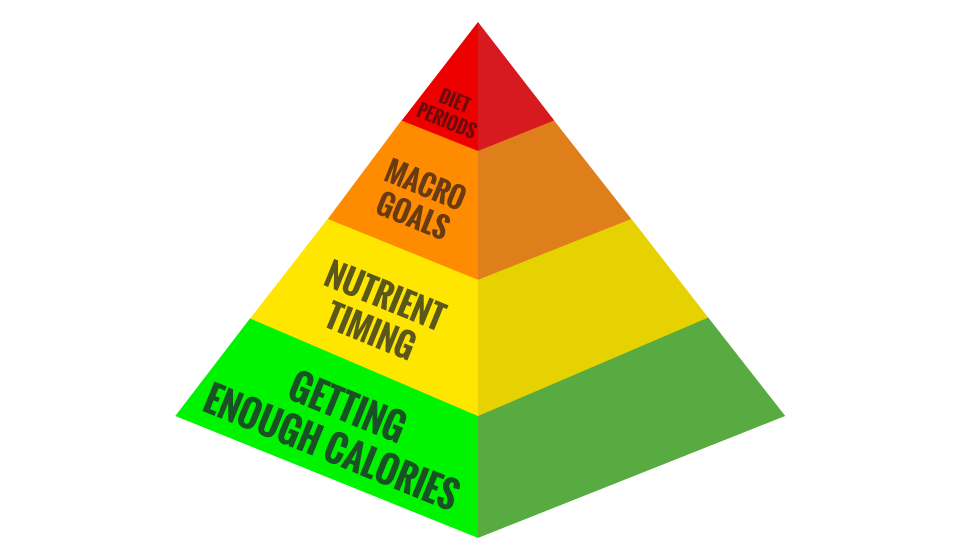

A Quick Look at the Complete Pyramid

In this article, I’ve chosen to represent the steps of good sports nutrition as a pyramid. I chose this shape for two reasons:

- It’s easy to see how each tier from bottom to top gives relatively less benefit in accordance to the sort of performance gain one should expect at each stage. You gain a lot more from eating adequate calories and timing your meals well than you do from dialing in your macro goals and periodizing your nutrition.

- It demonstrates how each tier builds upon the tier(s) before it. There’s no point in making macro goals if you’re not going to bother eating enough calories to begin with.

Bear in mind that this visual analogy can only be taken so far. There are numerous other aspects to good sports nutrition that are left out here, such as food choice, supplementation, hydration and so on. That being said, here’s the pyramid:

Good sports nutrition—nutrition designed to increase both short- and long-term performance—requires you first eat enough calories to fuel your performance and recovery, then to time your fuel optimally, then choosing the best fuels for your goals, and finally matching your fueling needs to your training. The lower tiers build to the higher tiers and cannot be rearranged without losing some efficacy in the process.

Now, let’s look at each tier in turn.

Tier 1: Getting Enough Calories

Climbing is a sport, climbers are athletes, and all athletes are fueled by calories. In Formula 1, you don’t spare the gasoline if you want to race your best; as a climber, you can similarly expect better performance when you fuel your body adequately.

Climbing is a sport, climbers are athletes, and all athletes are fueled by calories. In Formula 1, you don’t spare the gasoline if you want to race your best; as a climber, you can similarly expect better performance when you fuel your body adequately.

Some people argue that athletes are good at self-regulating their caloric intake; I disagree. Most athletes are good at regulating their weight, but this is much different than regulating one’s caloric intake. As I wrote about in a recent article, there is a wide gulf between the number of calories one must eat to lose weight and the number of calories required to gain weight (including muscle). When left to their own devices, an athlete may stay within that weight maintenance zone, but it’s unlikely they’ll be eating near the far end of that zone—the end that provides the greatest benefit—unless they’re actively trying.

Therefore, it’s worth putting a little effort into determine your ideal caloric intake.

I cover the process much more in-depth here, but the basics of determining your ideal caloric intake are these:

- Determine your resting metabolic rate (RMR), either using the formula here or with an online calculator.

- Multiply your RMR by 1.2 to get the total number of calories burned on a typical sedentary day.

- Add calories burned from activity estimates on a day-to-day basis.

You can also use a larger multiplier based on your average weekly activity level rather than the sedentary rate of 1.2 (again, see this article for more info) if you don’t know or don’t want to estimate your calories burned from activity on a daily basis.

This is your estimated caloric need—but it must be tested before committing to stone. Over the next week, weigh yourself routinely to establish a trend. If you lose weight (which is unlikely), add more calories. If you gain weight, subtract calories. If you maintain weight—and this is the critical bit!—add calories. Keep adding calories until you finally begin to gain weight, and only then should you back them off to just low enough to avoid gaining weight. Of course, if your goal is muscle gain, then you’d want to take that figure and increase it even further (a safe estimate is 5% further).

It’s pretty easy to calculate your RMR, even if you do all the math yourself; it’ll take less than 5 minutes, a paltry commitment for better performance. The frustrating part is that you’ll also need to measure your daily calories, at least for a few days, to ensure you’re hitting your target. Bear with it, though—diet logging sucks (it really does), but use the time to develop an internal idea of what such and such amount of food/calories looks like on your plate. Once you have a good idea, you can stop measuring it daily and just check from time to time to make sure your aim is still true.

The beauty of eating enough calories is that it’s easy and yields a tremendous benefit, regardless of what form those calories actually come in (at least assuming a regular mixed diet). Your energy will be higher, you’ll recover faster, and you’ll perform better. It’s only the beginning though. You can gain still more by timing your calories, as well.

Tier 2: Nutrient Timing

Nutrient timing is a fancy way of describing your daily eating pattern. It asks the following questions:

Nutrient timing is a fancy way of describing your daily eating pattern. It asks the following questions:

- How often do you eat?

- How much food do you eat per meal?

- How do your meals interact with other activities in your life?

I’ve discussed at length one of the cornerstones of nutrient timing, which is protein frequency. Basically, you should aim to get at least 20 grams of protein every 3-4 hours as that accounts both for how much protein it takes to maximally trigger muscle protein synthesis as well how long it takes your muscles to “cool down” and need another dose. With just this in mind, we can see that there’s a benefit for athletes consuming smaller meals more frequently (though a “smaller meal” for an athlete may be “normal” for a less active individual!).

Nutrient timing is also important to consider for carbohydrates. Regardless of the overall carb content of your diet, whether 15% or 75%, it pays to concentrate some carb intake during and around exercise because that’s when our body has the greatest need for them (for climbers, I typically recommend 45-60 grams per hour of exercise). The remainder should be spread out evenly amongst the rest of your meals.

EXAMPLE: If you had a hypothetical total carb load of 500 grams in a day and spent 3 hours climbing, you should consume about 135-180 grams of carbs immediately before, during, and after exercise (let’s average it 160 grams) and then spread the other 340 grams between your other meals. If you typically eat five meals or snacks in a day, that works out to about 70 grams per meal, or about 1.5 cups of most starchy carbs.

I’m getting ahead of myself, though—if you’re not counting macronutrients, you’ll be hard-pressed to divide them into neat blocks. Even if you don’t count macronutrients, though, it’s worth following some basic rules of nutrient timing:

- Eat 5-6 meals per day, spacing them 3-4 hours apart.

- Eat a high-protein item in every meal and snack.

- Eat more carb-rich foods during and around exercise.

With just these three tips, you’ll get even more benefit out of the calories you’re eating (assuming you’re eating enough calories to begin with). If you don’t mind counting macros, though, you can do even more with nutrient timing.

Tier 3: Macronutrient Goals

It was a toss-up whether macro goals should be the second or third tier on the pyramid, but ultimately I decided that nutrient timing is slightly more important and deserves more focus. Also, timing meals requires much less effort than measuring macros, so it made more sense to place nutrient timing before macro goals.

It was a toss-up whether macro goals should be the second or third tier on the pyramid, but ultimately I decided that nutrient timing is slightly more important and deserves more focus. Also, timing meals requires much less effort than measuring macros, so it made more sense to place nutrient timing before macro goals.

That being said, setting macro goals is a close third and not altogether much more effort (at least long-term).

Depending on the type of climber you are, your basic macronutrient goals will differ. For a better idea of what macronutrient goals I think each type of climber does best on, read this article—but in general, the longer you’re on the wall actively climbing, the more carbohydrates (and less fat) you proportionally need in your diet. For most climbers, this means a daily diet that…

- Contains 100-120 grams of protein (but more realistically 130-160, so you’re not weighing your food down to the gram to ensure adequate protein)

- Is 55-65% carbohydrate.

- Is 20-30% fat.

As with the first tier of our sports nutrition pyramid, counting macros requires you to measure food intake via diet diaries for a few days—and as before, you should use the time to get an idea of what different amounts of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats look like on your plate. Once you’re confident you can visually measure x, y, and z amounts of protein, carbs, and fats, then you can stop measuring your meals and just perform a check-up from time to time to keep your eyes honest.

To be certain, there’s no point in measuring macros unless you’re eating enough calories in the first place and, ideally, timing your meals well. If you are eating adequately and timing nutrients, though, then you can dial in your macro goals to eke the most out of your diet performance- and recovery-wise, at which point there’s only one step left: diet periodization.

Level 4: Periodize Your Diet (to Your Training)

Diet periodization only makes sense in the context of training, so before we discuss it we need to briefly discuss training. Similar to what we’ve done in this article, we can imagine training as a pyramid consisting of the following steps, each building on the previous:

Diet periodization only makes sense in the context of training, so before we discuss it we need to briefly discuss training. Similar to what we’ve done in this article, we can imagine training as a pyramid consisting of the following steps, each building on the previous:

- Climbing Enough: Simply getting on the wall frequently enough to improve.

- A la Carte Side Training: Doing nearly any sort of climbing-specific side training, like campusing, hangboarding, or 4x4s.

- Training Routines: Adhering to a training schedule instead of just training randomly.

- Training Periodization: Mixing your training up to prevent plateaus and work different aspects.

The final tier of our training pyramid—a tier that only a small percentage of climbers actually dedicate themselves to—requires you to change your training routine frequently. This periodization may consist of different phases (like strength—>power—>power endurance—>general fitness) or just different training protocols (campusing—>hangboarding—>systems wall), but regardless of the specifics it changes the core structure of your workout and therefore the overall optimal dietary requirements. This is what I’m referring to when I talk about diet periodization.

At its heart, diet periodization is the synchronization of your diet to your training; it means committing to reassessing every other step of the pyramid whenever your training goals change. If your training routine is meant to maximize strength gain, you increase your calories to match that. If you’re working power, you increase the relative presence of carbohydrates to amply fuel anaerobic energy systems. If you’re trying to lean up, you cut calories. Regardless of the change, you’re doing the work to match diet to training.

Outside of the context of training, diet periodization makes no sense; therefore, if you’re not currently periodizing your training, there’s no benefit to periodizing your diet. If you are periodizing your training, however, diet periodization is worthwhile.

How Far to Ascend: What’s Your Goal?

One last thing we should discuss: what makes sense for you? Every step offers a benefit—but when does the work become too great for the benefit received? Ultimately, that depends on you and your climbing habits.

Sports nutrition is just a piece of the puzzle, and in many ways it only makes sense to put as much effort into it as you put into any other aspect of your climbing. If you struggle to simply get out and climb enough, nutrition will only get you so far—you need to climb and train more to reap the performance benefits of a great diet, though you’ll still likely do well to be cognizant of your total caloric load (and adjust it accordingly). If you train on occasion, it’s worth timing your nutrient intake to maximize performance and recovery for those training sessions. If you’re dedicated to your training, you should also be dedicated enough to your diet to ensure you’re getting the most benefit from your training.

Basically, ascend as far up the sports nutrition pyramid as you do the training pyramid (and maybe a step further, if it’s not too much of a bother).

If you match your sports nutrition to your training, you’re all but guaranteed to benefit as much as can be expected—and anytime the two become out of sync, you can expect the other to hold you back. When you find yourself putting much more effort into one or another, it’s time to reassess your priorities and bring them back in line.

Become a Patron of Climbing Nutrition!

This is not part of the above article, and I understand completely if you browse on without reading this. If you have another minute, though, I would greatly appreciate it!

This is not part of the above article, and I understand completely if you browse on without reading this. If you have another minute, though, I would greatly appreciate it!

I currently write 2-3 articles a month on a variety of climbing- and nutrition-related topics. I plan on continuing to write at least this many articles, but I also want to start branching out and providing more in-depth feature-type articles and services. The critical part, though, is that I want to offer these high-value features for free and not sequester them behind a paywall, all so that any climber with a question about nutrition can easily get a scientifically accurate answer.

To this end, I’ve launched a Patreon campaign to help Climbing Nutrition become even better. Simply put, Patreon is crowdsourced funding in the form of patronage. Through the Patreon website, you agree to donate an amount of your choosing on a monthly basis—you become a patron of Climbing Nutrition—and in return I get financial security and the ability to plan for the site long-term. As Climbing Nutrition reaches higher levels of funding, I’ll have the time (because I’ll have to work my other job less) and resources to bring some of my visions to life, to the benefit of everyone.

Of course, it’s your choice. Climbing Nutrition is and always will be free, and I know that 99.5% of people reading this plea will not become a patron. If you’re a part of that 99.5%, I’m grateful that you’re here reading my articles, and hopefully you’ve improved your diet and climbing as a result. I do hope you’ll consider becoming a part of that 0.5% that’ll help bring Climbing Nutrition to the next level, though, because I can’t do it without you!

Thank you for taking the time to read this petition, and if you think you can help me out with Climbing Nutrition, you can learn more about my Patreon campaign here!

Sincerely,

Brian

Thanks for your ongoing articles – I find them extremely insightful. I have a question around the ‘Getting Enough Calories’ element. I’ve worked out my RMR and also the calories burnt during exercise, and if I’m climbing three days a week, one on one off. Do I need to hit my caloric goals on the days that I’m climbing or the day after? Because the day after climbing I feel like eating everything.

You should aim to meet your caloric goals on both active and rest days. Your overall need will be greater on the active day (because you’ll be adding in the extra calories burned from exercise), but muscle recovery is a calorie-intense process that takes at least 24-48 hours—so having enough calories even on days you don’t exercise is important, too!

Hi! Thanks for the insightful article. I have one practical question, though. Say I am optimizing my diet during a training cycle that aims at building up muscle. How would I know if weight gains are due to too many calories or muscle build-up? Clearly one would literally see the difference if one gains 10kg but it would be hard to tell if we are talking 1-2 kg, right? Any thoughts/experiences on that?

Merci

To a certain degree, you have to take it on faith—at least unless you have access to some accurate method of body fat analysis (DEXA, hydrostatic weighing, air displacement plethysmography, skin folds/ultrasound measured by an experienced practitioner). That being said, you can be relatively certain you are gaining muscle as opposed to fat if you eat to the level that you’re only gaining a half pound to pound a week (0.25-0.5 kilograms). Depending on your training, experience, and muscle groups worked, this is a reasonable number to shoot for. Of course, even the most regimented gaining diet will lead to a small increase in body fat, so it’s ultimately a question of ratios: how much muscle are you gaining for each unit of fat? Again, at the 0.5-1.0 pound (0.25-0.5 kilogram) level, it’s likely to be more muscle and less fat, but if you’re in the range of 2 pounds per week (1 kilogram), it’s likely to be a decent portion of fat as well.

Sorry I cannot be more specific, but it does come down to a number of personal factors in the end!