It’s that time of year, at least here in the northern hemisphere, when climbers start shrinking from the heat. This past weekend at Rocky Mountain National Park, at an elevation of almost 10,000 feet (about 3,000 meters), the temperature was over 75° Fahrenheit (24° Celsius)—and it was actually a “cool” day, at least down in valley where “hot” has meant temperatures nearing 100° F (38° C).

Obviously, heat isn’t great for climbing performance. Actually, heat isn’t great for athletic performance in general. While climbers may focus more on how sweaty their hands get as temperatures spike, all athletes suffer from a much more insidious side effect of the heat: increased core temperature. As core temperature rises, performance falls.

Now, there’s not a lot we can do about the weather itself—but just because the temperatures are soaring doesn’t mean you have to hang up your shoes til autumn. You can be proactive about the heat and learn how to effectively cool yourself so your climbing stays strong all summer long.

A Brief Overview of Core Temperature and Performance

Why does heat cause us to flail, sweaty hands aside? Why do runners and cyclists have slower times in hot climates than cool climates, despite otherwise equal conditions? Why do we often get tired (sleepy even) just from being in the sun all day? The reason deals with our core temperature.

Our body regulates itself to run at around 98.6° F (37° C). When core temperature begins deviating from this norm, our body takes action to bring it back in line. For example, when we start to get cold, we shiver in order to produce heat. But while our body is very good at producing heat—our entire metabolism creates heat as a by-product—it’s less good at dissipating it.

When our core begins to get too hot, our brain sends a signal to our muscles to slow down, which it does by increasing our relative perceived exertion—basically, it makes everything seem harder. And because everything seems harder, we perform less well, even if what we’re attempting is normally in our range.

If that seems strange, think about your computer. Your processor runs smoothly in cool temperatures, but begins to slow down as the temperature rises. The slower-running processor produces less heat, and can thereby avoid reaching catastrophically high temps. If the processor was designed to keep running at full speed regardless of temperature, it would blow itself out, killing your computer in the process.

It’s the same idea with your body and brain—if your brain didn’t limit your body’s performance when core temperatures increase, your brain would eventually fry. So instead of letting the body go as hard as the muscles (which perform better when warm, actually) are capable of, the brain reels in performance to whatever level is necessary to keep itself safe.

The Best Ways to Beat the Heat, According to Science

If you want to perform your best, you need a cool core. Unfortunately, achieving that goal is not particularly easy, especially at the crag. Nonetheless, there are more and less effective ways to go about it.

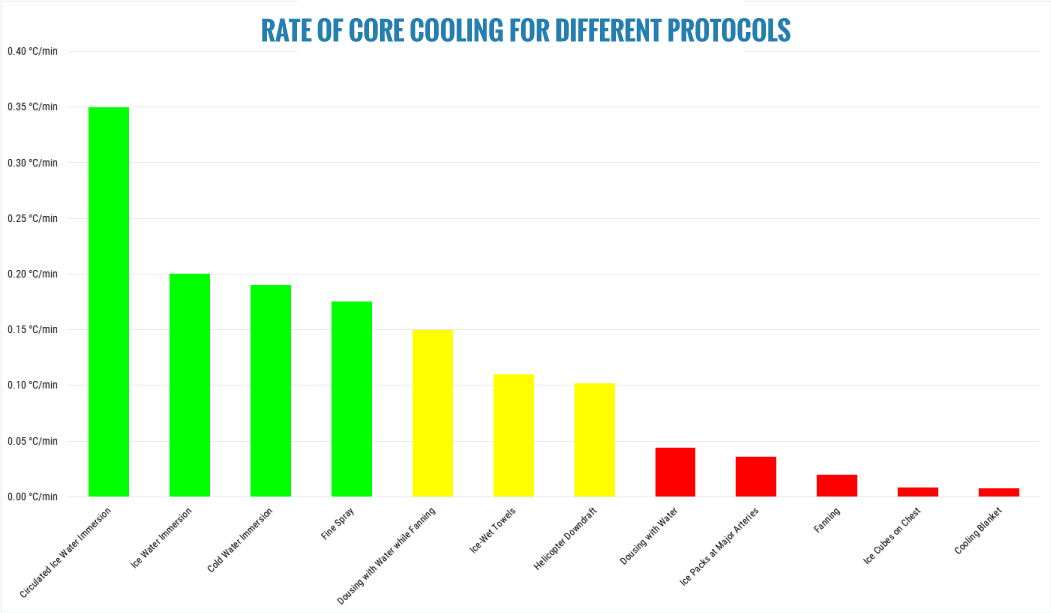

Below is a chart adapted from a systematic review on whole body cooling. I’ve simplified and condensed it to include only the most relevant (or humorous) entries:

McDermott BP, Casa DJ, Ganio MS, et al. Acute whole-body cooling for exercise-induced hyperthermia: a systematic review. J Athl Train. 2009;44(1):84-93. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.1.84.

The chart is color-coded green, yellow, red to indicate whether a particular method of cooling is “ideal”, “acceptable”, or “unacceptable” (according to McDermott et al.). The text is a bit hard to read, but here’s the gist of it:

- Ideal Cooling Methods significantly lower core temperature and do so rapidly (i.e., in minutes). They are mostly full-body immersions in water (the colder the better) and ideally are circulated in order to carry the heat away. The only method that isn’t full-body immersion is “fine spray”, which doesn’t have a lot of details attached to it but is presumably… well… a continuous, fine spray of cold water. Honestly, I wouldn’t opt for the fine spray, but it’d be so much more onerous to set such a system up that you’ll probably never even encounter it anyway.

- Acceptable Cooling Methods significantly lower core temperature but take tens of minutes to do so. Acceptable methods include dousing a person with water while fanning them (basically, throwing the contents of your water bottle on someone while fanning them), covering the body with frozen wet towels, and standing underneath an active helicopter rotor (because who doesn’t have access to a helicopter?).

- Unacceptable Cooling Methods either take hours to work or simply don’t work, and include just dousing, just fanning, and using localized cooling methods (or non-ice-based whole body cooling, like the cooling blanket). If you were wondering, gadgets like the neck cooling unit fall in this category and aren’t worth the money.

Looking at the above chart, there’s really only one useful recommendation for cooling down at the crag: jump in a body of cold water (preferably a circulating one, like a river) and chill there (fingers out of the water, please) for about 10 minutes so that you bring your core temperature down to normal (or even slightly below). Seems a bit unpractical, doesn’t it?—and that’s if there’s even water at the crag!

Thankfully, there’s another option not covered in the chart above: ice slurries.

Don’t Pack Water; Pack Ice Slurries

The above systematic review was released in 2009, before a slue of research was done on the ice/water emulsions known as “ice slurries”—think slurpees and frozen margaritas. Since then, many studies (1,2,3,4) have shown that not only are ice slurries effective at reducing core temperature, they’re nearly as effective as cold water immersion—and all they require is some planning ahead!

It may seem odd that ice slurries should be so effective, especially compared to hanging out in a frozen river for 10 minutes, but there’s some solid reasons for why we might expect it to be so:

- Ice slurries cool from the inside rather than from the outside. Remember that it’s not our muscles limiting performance, but our brain acting on feedback from our core temperature. When we attempt to cool the core from the outside in, the cold must penetrate through skin, fat, and muscle before achieving its goal; when we cool from the inside, there are fewer obstacles.

- Compared to water, ice can absorb significantly more heat—even compared to water that is within a degree of ice. This is because ice must go through a phase change to become water, and that phase change requires an extra bump of energy (heat) to achieve. Thus, ice slurries absorb significantly more heat (and therefore cool better) than water.

To effectively cool down, most studies used an ice slurry that had a volume of 7.5 grams per kilogram of bodyweight (roughly 0.11 ounces per pound), which is not a small amount—it’s about a half liter for a typical male. At least one study had success using only 1.25 grams of ice slurry per kilogram of bodyweight (0.02 fl oz per lb), though, which is only about a tenth of a liter or a half cup (4 oz) of slurry and much more easily achievable.

Even better, the study using the smaller amount of slurry used it as a post/intra-exercise cooling method (rather than pre-cooling) and measured maximal voluntary isometric contraction (which plays a significant role in climbing) as its test metric rather than endurance capability. Athletes who consumed the slurry brought their core temperatures down and were able to perform at a greater level again, despite being exhausted by the heat just before.

Of course, ice slurries carry one major downside: they can cause brain freezes. But aside from the occasional numbing pain in the head, there’s no reason not to bring all of your liquid in the form of an ice slurry—the slurry will be equally hydrating and help keep your core cool throughout the day, promoting better performance.

Making an Ice Slurry

Making an ice slurry isn’t hard, and only requires water, ice, and a blender. In my brief experimentation, I found that a 4:3 ratio of water to ice worked pretty well, though I was unable to make it quite as smooth as you would see from a frozen daiquiri machine.

Part of the reason why is that adding sugar and salt to the water lowers its freezing point, making it easier to get slush instead of just water and soft ice (alcohol helps even more, but isn’t recommended if you’re packing a slurry for climbing). Sure enough, when I added sugar, salt, and citrulline malate—basically, when I made a sports drink slurry—I was able to get a much more consistent slurry, even using a 1:1 ratio of ice to water (by weight).

Keep in mind that your slurry doesn’t have to win any awards for its smooth texture—all that it needs to be is smooth enough to ensure the ice can flow down your gullet and into your stomach. As long as you can bring the ice into your body, the slurry will be effective.

It’s Hot, so Keep Cool

Climbers tend to do their best climbing in the cool (or even cold) parts of the year. Part of the reason is skin- and sweat-based, but it’s also because performance suffers in the heat. It doesn’t have to suffer as much, though, if you’re willing to put some effort in.

Ice slurries are an easy, portable way to stay cool all summer long; all you need is to invest in some insulated water bottles and you can bring cooling with you anywhere. When you stay cool, you won’t suffer the same downgrades in performance that you normally would, and maybe that redpoint won’t have to wait until the weather cools in autumn.

Then again, if there’s a river near the crag you’re climbing at, it might be worth bringing your swimsuit as well!